____________________________

|

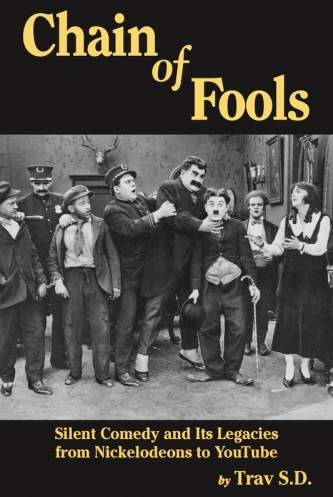

Buddy Ebsen working out 'character' movement with Walt Disney,

who often used the eccentrics for character inspiration. |

When I was first hired as a trainee at the Disney Studios at age 18, I had no idea how animation worked. But my early background in dance proved to be a bonus while working with my mentor, the great Eric Larson, one of Disney's

"nine old men." Not knowing any better, I would physically work out the movement (always dance), for the required personal tests. This instinctive ability to translate my extreme flexibility into cartoon characters was a match made in heaven, and I was soon hired as a full-time in-betweener on

The Rescuers while assigned to a veteran animator who best suited my style, the amazing Cliff Nordberg (

Three Little Pigs, alligators in

Peter Pan, Evinrude in

The Rescuers, etc.), renown for his over-the-top, character-driven animation.

I had just discovered and was studying eccentric dance and immediately saw a powerful connection. What astonished me most was that the process in creating character, building a gag, and making a step funny was virtually the same between the eccentric dancer and the animator. Their language was identical! I could not wait to get back to Disney and tell Eric, who only chuckled and mentioned that these dancers had been a staple of inspiration for many animated characters from the early beginnings of animation.

It made perfect sense. Windsor McCay, an early pioneer in animation, toured the vaudeville circuit in 1906 as an animated chalk talk act, and followed in 1914 with a stage performance teamed with his

Gertie the Dinosaur, at that time breaking ground as one of the first developed personalities in a cartoon. Sharing the bill with the top eccentric dancers and witnessing their cartoonesque, exaggerated movement must have ignited character ideas as it had for many other aspiring animators.

|

| Ichabod Crane |

I had to learn more and was stunned when learning that my

eccentric mentor, Gil Lamb, turned out to be the spot-on model for Disney's Ichabod Crane in

Legend of Sleepy Hollow, as was Buddy Ebsen for Disneyland's

Country Bears. The link was getting stronger, as Disney artists Ken Anderson and Joe Grant spoke of the tremendous influence Chaplin had on animation. Grant himself began his career as a Keystone Cop and had used Eddie Cantor and Charlotte Greenwood often as models. The prolific animation historian and writer, John Canemaker, clarified this analogy with his great

documentary short of Otto Messmer, who first translated Charlie Chaplin into an animated character.

|

| With Ward Kimball |

As animation reflects our times, Chaplin's "tramp" character was introduced the same time as the animated personality was evolving, and much of Chaplin's movement was soon emulated by Messmer's early

Felix the Cat character. Vaudeville was a treasure chest of eccentric dancers and visual comedians and a bounty for animators to use as reference in their character work and still is.

I was still processing all this when the amazing Dixieland Band, the

Firehouse Five, comprised of animators Frank Thomas, Ward Kimball and other visiting musicians, began playing outside the commissary during lunchtime. I could not help myself and began executing a rip-roaring charleston on the black-top. At first a shock to the Disney employees trying to eat lunch as well as to the animation staff, it opened up a life-changing opportunity — animation choreography! I was soon working with Don Bluthe on

Pete's Dragon, and dancing as the dragon Elliott in the parking lot, while tapping into the eccentric character process with a foam tail pinned to my arse. I worked again with Bluthe in

Banjo soon afterwards. It was here that Disney allowed me to take an unprecedented leave to tour in Will B. Able's

Baggy Pants & Co. vaudeville/burlesque show, followed by Jim Henson's

Muppet Show, upon pleading how this rare opportunity would only strengthen my animation, which it certainly did!

Upon returning to Disney, I was thrilled to work on my alter-ego and hero, Goofy, the consummate eccentric dancer, in

Mickey's Christmas Carol, and then, again teamed with animator Cliff Nordberg, began work on

The Fox and the Hound, animating the owl, Big Mama, and using the broadest character movement we could possibly conjure. It wasn't long before the great animator Andreas Dejas called me in New York to stage the character movement in

The Emperor's New Groove. I was one step closer to bringing the eccentric style back into the animated cartoon.

I continued to animate and illustrate, while researching and studying eccentric dance, and when I made the decision to make this documentary, it was vital to film the animators themselves, discussing the eccentric dancer's role in the evolution of animation.

|

| Charlotte Greenwood |

Many are represented well in

Funny Feet: Richard Fleischer, son of Max Fleisher and a renown Director (

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; Dr. Doolittle) spoke of his uncle Dave Fleischer, a great comic dancer in his own right, as the model for the first rotoscoped character (1915),

Koko the Clown. Richard spoke of his sister (then dating a young Ray Bolger), and her eccentric dance act where she popped on and off the screen, and how his father, who loved eccentric dance, most likely modeled Olive Oyl from legmania dancer Charlotte Greenwood.

|

| Steppin Fetchit |

Animator Myron Waldman's interview details watching vaudeville/burlesque shows while creating

Betty Boop and

Popeye, and how Cab Calloway was the model for the "old man in the mountain" and other characters. Chuck Jones' interview was wonderful, detailing how he studied Chaplin, Laurel & Hardy and Keaton, but professed how Groucho's walk became a signature in creating Bugs Bunny!

|

| Buster Keaton |

Frank Thomas & Ollie Johnston spoke a great deal about the physical comedians' influence on their own work, specifically citing Chaplin, Laurel & Hardy, Red Skelton, and Buddy Ebsen. Ward Kimball elaborated on always searching for new walks, and how animator Art Babbitt's defining 360-degree walk for Goofy made him a star, and how Steppin' Fetchitt and Keaton played an enormous role in the development of Goofy's character movement and personality.

Joe Barbera, of

Hannah Barbara provided incredible details on teaming Gene Kelly with Tom & Jerry, and later, on their ground-breaking collaboration for

Invitation To The Dance. Al Hirschfeld, the renown

NY Times caricaturist, eloquently spoke of observing, then capturing in line art, all the great eccentrics that graced the NY stage, and how Bolger specifically was inspired in his own movement by Hirschfeld's illustrations.

And the tradition continues, as the next generation of animators (Andreas Dejas, Eric Goldberg and others) understand the importance of observing and tapping into these great 'cartoon' eccentric dancers.

The Princess and the Frog

It all came full circle when the talented animation directors John Musker and Ron Clements (

Aladdin, Little Mermaid) approached me to bring the eccentric tradition into their next animated feature,

The Princess and the Frog. I was thrilled to have the opportunity to again work with a wonderful animation team, and especially, to introduce this history, a pre-cursor to their own work, to the next generation of incredible hip-hop break dancers. The surprise was instantaneous and I pushed them hard to capture the extreme movement necessary for animation.

The result was the "reference" video below, This was the "Mama Odie" number (the 200-year-old blind sorceress), with two spoonbill birds in the background, which eventually they multiplied to make it look like a flock of birds in a choir. (It was a gospel-type number.) She pantomimes her sidekick, a boa snake which I staged like a boa feather. The key for me was to hire matching body types for the animated characters....so I was very specific on the audition call. I staged seven musical numbers and six dialogue sequences over all.

|

| Buddy Ebsen and the animation grid |

Before I even began, I sat with the directors and went over an animatic storyboard, frame by frame, so I could match precisely the sound effects, dialogue and musical punctuation. (As it is all recorded prior to any animation beginning). As you see here, every gesture (head tilt, arm swing, etc....) was broken down frame by frame, (24 drawings a second for feature quality) No motion capture or rotoscope — I staged each number per frame, then one as a looser version, and then a couple of variations on walks (very important) and then one with total improv (in case the performer had an idea, so just let them do what they do best!). They used all as reference only....so they would have the freedom to play with the choreography. Everything was shot against a grid, exactly as with Buddy Ebsen in this photo. It is also filmed in every variation....(overhead, below, side views, etc....)

Choreography to me is not just dance.....it is 'character'.....it's how a character sits, walks, gestures, and even more importantly....

not moves, which is sometimes more powerful. It is the art of pantomime...and I make my characters think....

why do you walk over there....

why do you sigh and slump....

why are you jubilant. There must be a reason for the movement. It's all about action and reaction.

What the animators taught me, I heard directly from Ray Bolger when we talked about

Once In Love With Amy. He said I had to have a reason for every move I made. It's all the same process, fascinating to me, between an animator and an eccentric dancer. When I worked with the clowns at

Cirque, it's something I saw quite a bit. They walk out and do their schtick, but I made them think about character. How your walk on stage is different than another....how your body language defines

who you are from the moment you step out onto that stage. Add to that a unique twist that becomes identifiable to your character, which your audience will identify you with. For example, for Dopey the animator Frank Thomas added a "hitch-kick" to his walk, which at first was an accident but became his trademark. All this is important: character, story, body language, and believability to your audience, so they can empathize with you. In animation

and eccentric dance, the rules are the same!

Funny Feet can help me imagine a dream to strengthen the relationship between dance and animation, training the two genres to inspire each other once again!

______________________________________

Click

here for Betsy's web site.

Click

here for all of her guest posts to this blog.

And stay tuned. More to come!