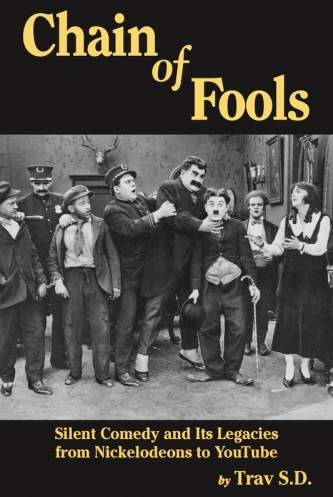

Chain of Fools

Silent Comedy and Its Legacies

from Nickelodeons to YouTube

by Trav S.D.

Trav S.D. —oddly enough named after his gritty home town in the middle of South Dakota's Badlands — is a so-good-he's-bad vaudevillian: a performer, producer, historian, popularizer, and blogger whose popular blog Travalanche is a must for the variety arts fan.

I remember when I first came across his book, No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book that Made Vaudeville Famous. I couldn't help but think "do we really need another history of vaudeville?" Then I read the book and discovered that the author was a really good writer, a prodigious researcher, and had a fresh slant on his subject matter. When I heard he was publishing a book on silent film comedy, I couldn't help but think "do we really need another history of silent film comedy?" Then I read the book and... yep, you guessed it.

|

| Trav S.D. |

Here's just a few of the things you will like about it:

• I highlighted something on almost every page. It's just chock full of info that was new to me and very interesting.

• He writes very lively and conversational prose, the kind I like to write but don't always succeed at. Nothing pedantic here. He searches for and almost always finds an interesting way to say what he has to say.

• He's very good at context. You really get the feeling what the work and artistic environment must have been for those creating this new medium.

• He makes a convincing case for silent film comedy as a unique art form and not just as a collection of funny performers.

• He doesn't pretend that every silent film comedy was wonderful.

• He's strong on the relationship between story and character.

• He appreciates what Paris and French culture meant to the arts and the growth of cinema.• He makes Mack Sennett very interesting.

• He has fresh insights on many of the comedians; Harry Langdon and Lupino Lane, to name just two.

Any weaknesses, quibbles, reservations?

• It's sparsely illustrated, and the discussion of individual films will have much more value if you have them on DVD or can find them online. Since he can't assume you do, a lot of space has to be devoted to plot summaries. He handles them well, but exposition is exposition.

• His pre-cinema comedy history is sketchy and is missing some pretty clear links between the two eras.

• Physical techniques aren't discussed in any detail.

• Max Linder's feature films are given short shrift, and some of the comedians of the 40s and 50s (e.g., 3 Stooges; Abbott & Costello; Ritz Brothers; Jerry Lewis) are a little too summarily dismissed for my taste.

• There are a few errors I caught. For example, Keaton's pole vault in College is lauded, but this was actually performed by gold medalist Lee Barnes, and it was apparently the only time (at least in the silent era) when Keaton used a stunt double. That being said, there's no reason to doubt the overall accuracy of the work.

|

| W.C. Fields in Sally of the Sawdust |

Here are a few samples of his excellent writing:

I tend to think of Keaton as a verb; Chaplin as a noun.

This principle of ultimate action, of perpetual motion, was not discovered overnight, but came gradually, experimentally, in the same way Jackson Pollock arrived at drip painting or Charlie Parker came to bebop. It was a process of taking matters a little further, a little further, a little further over dozens of films until Sennett hit a new comedy dimension that looked like universal chaos.

There was very little precedent for what Sennett would now attempt. This would be the first time in history a studio head would endeavor to staff an entire company with absurd types. Sennett's comedians resembled human cartoons: fat men, bean poles, vamps, men with funny mustaches, matronly wives and mothers-in-law wielding rolling pins and umbrellas; geezers with canes and long beards, bratty children with enormous lollipops. Diminutive heroes; terrifyingly large villains.

Keaton's character may have a place in society, but he realizes that this is no guarantee of security or even tranquiity. What about the safe that may fall on your head? Or conversely, the wallet full of money that may miraculously fall into your hands. Rich or poor makes no difference. Fate makes playthings of us all. Man plans. God laughs. Keaton seems to feel no need to comfort us about this. No one emerges to make things better. The world is cruel, capricious, barren of any special benevolence. It is this lack of faith or optimism perhaps that causes Keaton's comedies to speak more to our time than to his own, and made him a big hit with European audiences even as many Americans were scratching their heads.

______________________

You can buy Chain of Fools here.