[post 379]

"That's not funny!"

You've all been told that, right? You just finished loudly laughing at something — or maybe you did something you thought deserved a big guffaw — and instead of the laughs spreading like wildfire, you are shut down with a stern "that's not funny!" And of course this cuts both ways. As would-be comedy experts, most of us are pretty damn opinionated about the subject and may often find what passes for funny to be pretty lame indeed.

So who's right?

The obvious answer is that if you think it's funny, then it is — to you. Laughter is subjective, a matter of taste, cultural orientation, and individual psychology. You may really dig the Three Stooges, perhaps because of their sheer relentless anarchy; or you may dismiss them, perhaps because of a lack of subtlety in characterization and story. A matter of taste, yes, but also a matter of emphasis.

This recurring argument came up because of three recent comments to this blog by three experts in the field. Dominique Jando, renowned circus historian, clown teacher, and mastermind of the

Circopedia web site, wrote this about a video I posted of Ukrainian clown Kotini Junior:

Physically, Kotini is very impressive. Unfortunately, I cannot see anything in his character that is emotionally working — neither his makeup, nor his facial expressions. He is just manic and seems angry. That's probably why he is not well known: With a more engaging character (and possibly a more expanded repertoire), he would be working everywhere!

And here's the video:

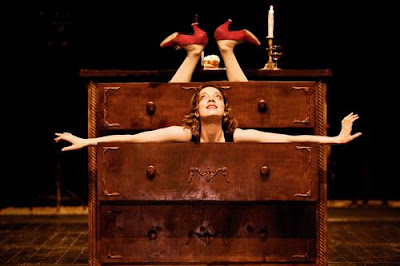

A video I posted of a ballet parody,

Le Grande Pas de Deux, and which I described as "very funny," elicited a similar response. First, here's the video:

Avner Eisenberg, aka

Avner the Eccentric, wrote "Enjoyed it, but… The cow looks real, but why is it there? They certainly can dance! But comedy? Not so sure."

Dave Carlyon, clown and circus historian, was more sure:

While this has some funny moments, I think it represents the problem that physical comedy and clowning often slide into. It piles on random bits, with little regard for relationship, reality, or internal logic.

Cow: Other than the sight gag, how does it fit anything? When the guy loses the gal, he does seem to consult it (6:00) but doesn’t look where the cow presumably told him to find her, instead simply making a conventional ballet move and going where the choreography indicated.

Purse: Why is this in it? She drops it and picks it up at random moments, not even fitting the music. Its only real purpose seems to be to hold confetti to toss (8:53), but even then, the execution is awkward and the timing is bad.

Relationship: It’s never clear how they fit together. Early, he tugs her (2:38) in a kind of comic bullying that fits the classic top banana / second banana, but other times they’re smoothly in sync. I could understand if they’re falling apart as a pair but these goofy moves are random. Sometimes they have no relationship at all: She spins till she’s dizzy (7:21-7:31) and he simply waits his turn (7:45), showing no concern for her, nor smugness that he’s better, nor even comic impatience waiting for his turn. He’s not a character in a comic piece, he’s just a dancer waiting for his cue.

Reality: The lack of a clear relationship is part of the larger failure of reality. He nearly kicks her as she crawls off (5:43, 5:48) — which is simply awkward choreography — but only 7 seconds later (5:55), he can’t figure out where she is.

Dance: It’s not good as dance. The traditional moves are often as awkward as the jokey ones, and the movement doesn’t always match the music. It seems likely that the choreographer thought what too many clowns and physical comedians do, “It’s comedy so anything’s okay.”

Parody: Even here it fails. Goofy moves interrupt classic dance moves but with no particular purpose, rhythm, or reason. The laughs hint at this failure: They’re sporadic, and often simply bursts of a laugh-like noise to indicate they got the joke.

The irony is that this mess is fixable. Gimme two hours with these two, and it’d have a comic structure, relationship, and consistent laughs.

Now the funny thing is that these three

éminences grises sound exactly like me. You may have noticed that I don't use this blog to criticize work that I don't like, but as my friends can tell you, these are the kind of critiques I annoyingly make after many a performance of movement theatre: "the character relationships are poorly defined, the narrative is weak" etc. etc. And when I teach or direct physical comedy, these are the elements I try to integrate with the more technical aspects, in the belief that the laughs will be deeper and more memorable when they're rooted in reality.

BUT....

There's another side to this argument.... maybe several.... so let me play devil's advocate here.

Audience Reaction

I sure heard some loud and sustained laughter, but if Christian Spuck's

Grand Pas de Deux really isn't funny, then why has it been in the Stuttgarter Ballet repertoire for a full 15 years now? Those Germans must have a weird sense of humor, right? Apparently not, because the piece has also become a worldwide success, including performances by the American Ballet Theatre. It was described by

Dance Magazine as a "witty, parodic gala favorite" and by the

New York Times as "a redeemingly funny sendup of ballet gala duets." I found a couple of bad reviews online, comparing it unfavorably to the spoofs of

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, but more common were comments such as "pure fun" and "brought the house down." In other words, a lot of people have indeed found this "very funny," without necessarily caring why the cow is there or how strong the relationship is between the characters. What gives? Are they just dumber than us?

You Had to be There

Some of it is situational: they're sitting in the audience in a fancy theatre, probably all dressed up, and certainly are not like the rest of us, at home in our underwear reading my blog. They've just watched some highly aesthetic ballet, performed more or less perfectly, and they're ready for comic relief. Of course it's funnier live and in that context.

Getting the Jokes

It's not funny if you don't get the jokes, and you may need to be a ballet aficionado who's been sitting in those same seats for half a lifetime to get most of them. Here's my evidence,

a review from the UK newspaper

The Spectator:

Another reference-ridden duet concluded the first part. Created in 1999, Christian Spuck’s Le Grand Pas de Deux is one of the very few successfully comic takes on ballet I have seen. In front of a reclining cow, a ballerina — complete with tutu, tiara, glasses and a red handbag — and her dashing partner dance to Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra, liberally quoting, in a variety of hysterically funny ways, from all the known classics. It is a firework performance, which ties in splendidly with the opening.

"Reference-ridden" and "liberally quoting, in a variety of hysterically funny ways, from all the known classics." Not only did this critic, certainly no country bumpkin, find it "hysterical" — which is a notch or two above "very funny" — but she also makes the point that it was constantly referencing specific moments from classical ballet. There's similar evidence from other critics: "Taking its cue from the classical Russian tradition, you can spot signature moves from

Swan Lake, Giselle and

Sleeping Beauty."

And: "A parody of many a pyrotechnic Grand Pas de Deux (and a quote from Giselle Act II)."

And: "The slapstick touches — flat feet, a ballerina in spectacles — are funny for anyone, while the sly satire will delight ballet aficionados." It's no wonder that this piece gets performed so much at gala benefits: it works best with a knowledgeable audience.

But what about that disappointing cow, so lifelike yet so inert? Bad comedy or an inside joke? Here's a guess: classical 19th-century story ballets are full of bucolic scenes, with farms and peasants and barnyard animals in the background, while in the foreground cavort the principal dancers, who clearly would be more at home in the royal palace. It didn't take me long to come up with these images from

La Fille Mal Gardée:

Holy cow, what's that I see in the background?

Vachement lifeless and inert? I rest my case, your honor!

In Spuck's parody, the cow doesn't have to be involved to be funny. Indeed, it may be funnier because it's simply and incongruously there, alone on a bare stage, representing all those other fake animals in all those other story ballets.

My point is this: just as you shouldn't call baseball "boring" if you don't understand the subtleties of the game, you can't critique a parody unless you're very familiar with what's being parodied.

The Intentional Fallacy

This term refers to the dumbass mistakes critics make when (according to more than one standard definition) they try to "judge a work of art by assuming they actually know the

intent or purpose of the artist who created it."

What we laud as great art today was often maligned as garbage when it first premiered because critics thought the artist's intention was to do what everyone else was doing, but not succeeding, rather than trying to break new ground.

Rotten Reviews, a compendium of scathing criticisms of work we now revere, gives a great perspective on this. The early impressionist painters got this treatment, as did most modern art movements, not to mention jazz and hip-hop.

Waiting for Godot was initially trashed because "nothing happened" and it didn't have a traditional beginning-middle-end narrative structure — as if that had been Beckett's intention, but he just couldn't figure out how to do it. Even Walter Kerr, champion and great appreciator of silent film comedy, haughtily dismissed

Godot as a "cerebral tennis match" when it opened in New York in 1956. It's a natural reaction, but one to beware of.

In this case, I think the intentional fallacy being made is the notion that the piece is or should be all about story and character relationship. The official line, at least since Aristotle, is that story is everything. It's how we make sense of our lives. And if you have academic training in drama, as Dave and I both do, then this is the way you are trained to think. A more cynical post-modern view is that story is at best an artificial construct to entertain an audience (and sell them a product), and at worst a tool that manipulates our emotions, brainwashing us into patterns of perception that sell a political product.

My argument would be more mundane: that the

Grand Pas de Deux is in fact

not about two characters trying to do a dance but screwing up and falling apart along the way. It is

not about their moment-to-moment psychology and motivation. For example, at some points we laugh because they do something clumsy, but at other points because they're clever enough to deliberately insert contemporary dance moves into the choreography. Yes, that's inconsistent characterization, but it's on purpose and doesn't matter. It's just two performers skewing ballet tradition from every conceivable angle with reckless abandon for maximum laughs. No one cares about a character arc. It's more of a collage than a narrative.

We all look for different things. I find it particularly interesting, as Robert Knopf points out in his book

The Theatre and Cinema of Buster Keaton, that the surrealists had no interest in the widely acclaimed narrative films of the 20s, preferring instead the work of Keaton and other eccentric filmmakers. Indeed, surrealist leader André Breton had a habit of visiting Paris cinemas, viewing fragments of films by chance alone,

"appreciating nothing so much as dropping into the cinema when whatever was playing was playing, at any point in the show, and leaving at the first hint of boredom... to rush off to another cinema where we behaved in the same way.... we left our seats without even knowing the title of the film, which was of no importance to us anyway."

Yeah, I know, we've all done that with our television's remote control, but the surrealists were looking for something specific, and it wasn't old-fashioned storytelling. Knopf writes:

Keaton is able to fill his narrative containers with a special substance, an amalgam of vaudeville, melodrama, optical illusion, and his unique vision of the world... Whereas classical critics view Keaton's films for the logic of their narrative structure, surrealist critics search for the ways in which Keaton questions the logic of the world. Keaton never intended to create surrealist films, yet the ways in which his films challenge logic, reason, and causality influenced the surrealists, who saw in his films and those of many of the silent film comedians an involuntary surrealism.

It wasn't just the surrealists. Dadaists, futurists, and the Russian avant-garde all looked to silent film and the variety theatre for new structures, ranging from dreamscapes to shocking cabarets to what Sergei Eisenstein called "a montage of attractions."

Which brings me to the clown Kotini Junior. He displays great dexterity with eccentric movement — reason enough for me to post his work on this blog — but as Dominique Jando rightly observes, he is manic and his character has no psychological depth. I agree, but I don't think that was his intention. I'm pretty sure that he does what he does as a conscious choice. He offers us not a sympathetic character who we're supposed to identify with, but rather an insane dream featuring a creature with a chair problem whose body frantically twists and warps in ways human bodies usually can't. It's a different approach, but one that the surrealists, with their insistence on the primacy of the dreamworld, might have enthusiastically embraced.

Or the Italian futurists, for that matter. Couldn't this quote from Marinetti's manifesto,

The Variety Theatre (1913), apply to Kotini?

"The conventional theatre exalts the inner life, professorial meditation, libraries, museums, monotonous crises of conscience, stupid analyses of feelings, in other words (dirty thing and dirty word), psychology, whereas the Variety Theatre exalts action, heroism, life in the open air, dexterity, the authority of instinct and intuition. To psychology it opposes what I call body-madness."

It's an extreme dichotomy and no doubt overly simplistic, but it's another example of alternative ways of looking at performance.

And not to beat a dead cow, but returning to our bovine friend one last time... it too could be seen in a surrealistic context. The cow could be funny because it's totally random, and the joke is on us because we expect it to be part of the action. Or as another joke goes: "How many surrealists does it take to screw in a lightbulb?" — "Fish."

Maybe if Dave (or Avner or I) re-directed

Le Grand Pas de Deux, the relationships and narrative would be stronger, but I wouldn't automatically assume the Stuttgart audience would like it any better. Maybe we would, maybe an audience of our picking would, but not necessarily most people, and certainly not everyone. And of course there's the danger of it becoming a lot less funny because we might lose a lot of the jokes that the audience is already laughing at.

Conclusion? There's more than one way to skin a funny bone. I'd say laugh at what you like.... because you will anyway.

LINKS:

• My

blog post about clown Kotini Junior.

• My

blog post about Christian Spuck's

Grand Pas de Deux.

•

Where all that wacky "what's so funny?" typography comes from.

[post 412]

[post 412]